Page 25 - C.A.L.L. #41 - Summer 2016

P. 25

two children in this

cabin, and with whom I

chatted about recent

New Yorker articles and

long-ago peyote

circles.

She and the others had

all come in their early

20s, from lives in quiet

East Coast suburbs and

California college

towns, to this place that

Robert Greenway, a

psychology professor,

had purchased with his

companion River. It was

not ‘‘dropping out,’’

argued River, in her

1974 book ‘‘Dwelling,’’

but an active search for

‘‘a new pattern of -

living’’ that does not

‘‘rip off the planet or

any of her inhabitants.’’

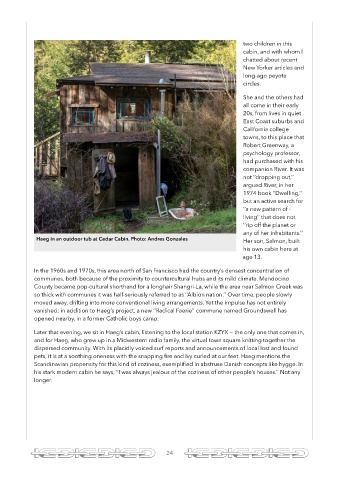

Haeg in an outdoor tub at Cedar Cabin. Photo: Andres Gonzales Her son, Salmon, built

his own cabin here at

age 13.

In the 1960s and 1970s, this area north of San Francisco had the country’s densest concentration of

communes, both because of the proximity to countercultural hubs and its mild climate. Mendocino

County became pop-cultural shorthand for a longhair Shangri-La, while the area near Salmon Creek was

so thick with communes it was half-seriously referred to as ‘‘Albion nation.’’ Over time, people slowly

moved away, drifting into more conventional living arrangements. Yet the impulse has not entirely

vanished; in addition to Haeg’s project, a new ‘‘Radical Faerie’’ commune named Groundswell has

opened nearby, in a former Catholic boys camp.

Later that evening, we sit in Haeg’s cabin, listening to the local station KZYX — the only one that comes in,

and for Haeg, who grew up in a Midwestern radio family, the virtual town square knitting together the

dispersed community. With its placidly voiced surf reports and announcements of local lost and found

pets, it is at a soothing oneness with the snapping fire and Ivy curled at our feet. Haeg mentions the

Scandinavian propensity for this kind of coziness, exemplified in abstruse Danish concepts like hygge. In

his stark modern cabin he says, ‘‘I was always jealous of the coziness of other people’s houses.’’ Not any

longer.

! 24