Page 24 - C.A.L.L. #41 - Summer 2016

P. 24

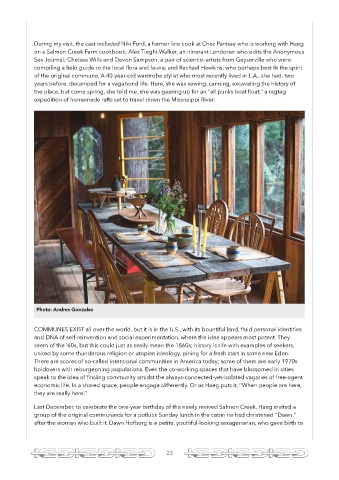

During my visit, the cast included Niki Ford, a former line cook at Chez Panisse who is working with Haeg

on a Salmon Creek Farm cookbook; Alex Tieghi-Walker, an itinerant Londoner who edits the Anonymous

Sex Journal; Chelsea Wills and Devon Sampson, a pair of scientist-artists from Geyserville who were

compiling a field guide to the local flora and fauna; and Rachael Hawkins, who perhaps best fit the spirit

of the original commune. A 40-year-old wardrobe stylist who most recently lived in L.A., she had, two

years before, decamped for a vagabond life. Here, she was sewing, canning, excavating the history of

the place, but come spring, she told me, she was gearing up for an ‘‘all punks boat float,’’ a ragtag

expedition of homemade rafts set to travel down the Mississippi River.

Photo: Andres Gonzales

COMMUNES EXIST all over the world, but it is in the U.S., with its bountiful land, fluid personal identities

and DNA of self-reinvention and social experimentation, where the idea appears most potent. They

seem of the ’60s, but this could just as easily mean the 1860s; history is rife with examples of seekers,

united by some thunderous religion or utopian ideology, pining for a fresh start in some new Eden.

There are scores of so-called intentional communities in America today; some of them are early 1970s

holdovers with reburgeoning populations. Even the co-working spaces that have blossomed in cities

speak to the idea of finding community amidst the always-connected-yet-isolated vagaries of free-agent

economic life. In a shared space, people engage differently. Or as Haeg puts it, ‘‘When people are here,

they are really here.’’

Last December, to celebrate the one-year birthday of the newly revived Salmon Creek, Haeg invited a

group of the original communards for a potluck Sunday lunch in the cabin he had christened ‘‘Dawn,’’

after the woman who built it. Dawn Hofberg is a petite, youthful-looking sexagenarian, who gave birth to

! 23