Page 30 - C.A.L.L. #47 - Winter 2020/2021

P. 30

communal living and intentional communities. It may be that some of the ideas being tested in

these communities can create the blueprints for the towns and cities of tomorrow.

Alternative lifestyles

There is some evidence that intentional communities are formed as responses to the

concerns of society at any given time.

Back in the 1970s, many new communities were formed as a backlash to mass urbanisation

and industrialisation. Such groups bought up rural property, often with land, and attempted a

“back to the land” lifestyle informed by ideas of self-sufficiency.

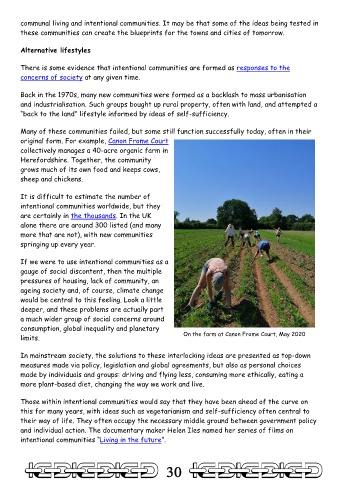

Many of these communities failed, but some still function successfully today, often in their

original form. For example, Canon Frome Court

collectively manages a 40-acre organic farm in

Herefordshire. Together, the community

grows much of its own food and keeps cows,

sheep and chickens.

It is difficult to estimate the number of

intentional communities worldwide, but they

are certainly in the thousands. In the UK

alone there are around 300 listed (and many

more that are not), with new communities

springing up every year.

If we were to use intentional communities as a

gauge of social discontent, then the multiple

pressures of housing, lack of community, an

ageing society and, of course, climate change

would be central to this feeling. Look a little

deeper, and these problems are actually part

a much wider group of social concerns around

consumption, global inequality and planetary

limits. On the farm at Canon Frome Court, May 2020

In mainstream society, the solutions to these interlocking ideas are presented as top-down

measures made via policy, legislation and global agreements, but also as personal choices

made by individuals and groups: driving and flying less, consuming more ethically, eating a

more plant-based diet, changing the way we work and live.

Those within intentional communities would say that they have been ahead of the curve on

this for many years, with ideas such as vegetarianism and self-sufficiency often central to

their way of life. They often occupy the necessary middle ground between government policy

and individual action. The documentary maker Helen Iles named her series of films on

intentional communities “Living in the future”.

30