|

A panoramic view of Drop City in 1966; the large complex to the right housed a kitchen/dining area, a film workshop, bathrooms and a shower, and a TV loft.

Clark Richert

|

On May 3, 1965, an artist named Clark Richert became part owner of a six-acre goat pasture in Las Animas County, a few miles northeast of Trinidad. His former college buddy Gene Bernofsky wrote the $450 check for the land, and Richert paid for the utility hookup that would bring running water to the property. The deed changed hands on Richert’s 24th birthday.

Not that Richert and Bernofsky — or their other original partners in the venture, Gene’s wife, JoAnn, and fellow artist Richard Kallweit — were hung up on who owned what. The community they hoped to build there, Drop City, would be a place where creative people could share meals and ideas, where everybody had a say and nobody ran the show, a kind of artist colony without landlords or hassles.

“The only rule we had was that there are no bosses,” Richert recalls.

Over the next five years, Drop City metamorphosed into something no boss could control. Hailed as the first rural hippie commune, it drew hordes of consciousness-seekers and lookie-loos and triggered the creation of a string of other, mostly short-lived communes across the Southwest. Its distinctive clump of dome homes, inspired by the work of Buckminster Fuller and making use of materials scavenged from junkyards, won design awards; the shaggy people inside the domes became the subject of intense focus by mainstream-media squares, who erroneously assumed that the place’s name was a reference to dropping out or dropping acid.

David Perkins (with microphone) moderates a La Veta panel of commune veterans. From left: Chip and Elaine Baker, Pat McMahon, Dean Fleming, Nancy Brooks, Jeff Briggs.

David Perkins (with microphone) moderates a La Veta panel of commune veterans. From left: Chip and Elaine Baker, Pat McMahon, Dean Fleming, Nancy Brooks, Jeff Briggs.

At its peak, Drop City was a required stop for sociologists, filmmakers, pilgrims, putative gurus and anybody else seeking to fathom or exploit the counterculture, hippiedom and the whole ’60s thing. One of the commune’s core members, the poet Peter Rabbit, wrote a quasi-underground memoir — issued in 1971, by a publisher better known for gay stroke books with titles such as Twelve Inches With a Vengeance — that helped to cement Drop City’s growing reputation as a sinkhole of dope, free love and general freakiness. Then, like much of what seemed so Now, it was over, gone, vanished.

But in recent years, just like the salvaged car tops that covered its domes, the legend of Drop City has undergone some recycling and repurposing. To mark the fiftieth anniversary of its founding, this past month there have been panels and speeches, art and photography shows in venues across southern Colorado, gently debunking some of the media myths and reappraising the group’s legacy. No easy task, certainly, but the retrospectivists — folks who not only survived the decade but actually remember it — seem up to it.

A recent panel in La Veta featured an array of hardy ex-flower children, several of whom had spent time at Drop City before launching the Libre commune in Gardner, Colorado. The packed audience featured a strong run of gray beards and snowy white ponytails, floppy hats covering bald pates, tie-dyed shirts on bony chests, and a smattering of bemused millennials. But they all listened raptly as moderator David Perkins, also known as “Izzy Zane,” described what it was like to be a self-proclaimed anarchist ducking the draft in ’68, hustling up a grant to study “utopian communities in the United States,” and ditching Buffalo, New York, for New Buffalo, New Mexico, to pick up the commune groove. “We gravitated to Drop City pretty quickly,” Perkins said. “It was a very exciting time. I’ve never regretted it. For one second. Ever.”

“Drop City was always an experiment,” added panelist Dean Fleming, Libre’s 82-year-old founder. “They didn’t last long. Now there’s a celebration for this place that bit it in four years’ time. But I think of it as a seed.”

“We found all these rocks up there. We started painting the rocks. Then we started dropping them off the roof. We called them ‘droppings.’"

Richert, who now lives in Denver and didn’t attend that panel, says the origins and intentions of the “experiment” have been greatly misunderstood. As an art student at the University of Kansas, Richert had become fascinated by the creative ferment at Black Mountain College a decade earlier, including the improvisational performance art, later known as “happenings,” staged by John Cage and others. When Gene Bernofsky, a psychology student with an artistic bent, moved into Richert’s loft in Lawrence, the two began developing what they called “drop art.”

“We had regular access to the roof of the building,” Richert explains. “We found all these rocks up there. We started painting the rocks. Then we started dropping them off the roof. We called them ‘droppings,’ and they became more and more elaborate.”

Bernofsky and Richert began dropping art into stranger situations, inviting public participation. They placed an ironing board on a sidewalk, the iron “plugged” into a parking meter. They set out an inviting breakfast on a table, then waited for a passerby to partake. They talked about establishing a place where artists could work unfettered, collaborate at will and see what happened, a place they would call Drop City.

“In my mind, it was an artists’ community,” Richert says. “Gene was calling it a ‘new civilization.’”

Richert went on to pursue graduate work at the University of Colorado. Gene and JoAnn Bernofsky went to Africa, scouting possible locations for a new civilization. Ultimately, though, the group settled on the goat pasture near Trinidad. And by the time the purchase went through, Richert knew what kind of structures he wanted to erect there. The initial plan had been to build A-frames, but Richert had seen Buckminster Fuller’s slides of geodesic domes during one of Fuller’s lectures at CU’s Conference on World Affairs — and quickly became intrigued by the possibilities of domes as low-cost but stable housing.

Drop City would eventually feature a variety of dome designs, including one large building, composed of three intersecting domes, that served as a common area and contained the only plumbing, including two bathrooms and a shower stall. The first dome was forty feet in diameter and took shape over the first winter on the property. “I had to build it by myself,” Richert recalls. “Everybody else left.” After Richert finished the wooden structure, Steve Baer, who designed many of the Drop City domes, covered the skeleton with salvaged auto steel — “which strengthened it enormously,” Richert notes.

The domes cost little to produce; most of the materials were begged, “borrowed,” donated or liberated. Soon word got out about a gathering of “Droppers” in southern Colorado where you could live practically for free, growing your own food or combing garbage dumps for the perfectly good stuff middle America was throwing away. Animosity in the county quickly mounted against the dirty hippies camping out and signing up for public assistance, but Richert says a few arrivals got food stamps for only a short time before an outraged bureaucrat cut them off, telling them they “have no right to be poor.” Yet as curiosity about the new settlement increased, so did opportunities for the Droppers to collect speaking fees. Peter Rabbit organized numerous visits to schools and campuses, where members showed films they made and a spinning, strobe-lighted painting created by Richert and others. The group also designed Day-Glo posters that were marketed globally by a firm in New York.

“Our main source of income was really art,” Richert says. “For the first three years, Drop City was mainly artists, filmmakers and writers.”

One of those who drifted through was Fleming, a surfer turned beatnik turned painter, whom Richert had met in New York. At the La Veta panel, Fleming recalled being impressed with Drop City but perceiving more chaos than art in the works. “Their principle was, ‘Everybody’s welcome’ — which, in America, is a disaster,” he quipped. The forty-foot dome, he added, “leaked like a sieve. We built ours [at the Libre commune] for $700. The Droppers thought that was real bourgeois. But my dome is still there!”

“There’s this myth that we got overwhelmed by hippies and that’s what destroyed Drop City. Our biggest problem was that we didn’t make enough money."

Media reports about Drop City tended to dwell on the “hippie lifestyle” of its occupants rather than its artistic mission. Richert recalls one overture from the gray-suited minions of CBS News. The Droppers agreed to be interviewed on two conditions: the report would not refer to them as hippies, and it would make no reference to dropping acid. But when the piece aired, it began with a long-haired ringer the television crew had brought out to the site so he could pop a pill in front of the camera, as the dour reporter explained: “This is a Drop City hippie dropping acid.”

Acid was surely dropped on occasion at Drop City. But Richert maintains that the accounts of wild sex and copious drug use, including those found in Rabbit’s book, are greatly exaggerated. More brazen acts of getting high could be found on any college campus in America. And it wasn’t as if a sudden influx of stoned, lazy hippies drove the operation into the ground, Richert insists. He never saw more than forty people in residence at a time, while the more stable population tended to hover around fourteen people. “There’s this myth that we got overwhelmed by hippies and that’s what destroyed Drop City,” Richert says. “Our biggest problem was that we didn’t make enough money. I didn’t leave because I thought things were out of control. But when I visited a couple of years later, the place was really on a downward trend.”

Richert left in 1968, after a doctor told him his pregnant wife needed more protein than the Drop City diet, heavy on rice and beans, could supply. He thought at the time that he would be moving back some day, but he never did. The Bernofskys had left earlier. Rabbit stuck around for a couple more years before finally splitting to help Fleming launch Libre. His book paints a grim picture of Drop City in its latter days: “We got lost in a reflected image of ourselves…. People were crashing all over the Complex. Nobody knew anybody else. People would stay a month or so, get themselves a little straight and travel on. The Droppers were going on the same trip over and over again: coolin’ out runaways, speed freaks and smack heads, cleaning up after them, scroungin’ food for them, playing shrink and priest confessor…. Instead of a community of people dedicated to getting it together on the highest possible level, Drop City became a decompression chamber for city freaks.”

In the early 1970s, what was left of the community quickly deteriorated. The domes were defaced with graffiti, vandalized, torched. The titular owners of the property, a nonprofit group of artists that included Richert, found that they couldn’t manage it from afar. The group ended up selling the property to a neighbor, who turned it into a truck-repair facility.

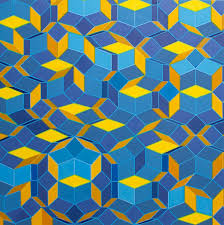

"S-Quanta," by Clark Richert, acrylic on canvas. Clark Richert

"S-Quanta," by Clark Richert, acrylic on canvas. Clark Richert

But that was not the end of what Drop City began. The panel in La Veta bristled at the idea that the commune movement was some kind of failed experiment; Libre, for example, is still a happening place, billing itself as the oldest continuously operating hippie commune in the nation. “We lived for twenty years off the grid,” boasted Perkins. “We worked so hard for a bunch of lazy hippies. We weren’t any flash in the pan. We must have done something right.”

Panelist Pat McMahon helped start the New Buffalo commune in 1967, which involved “cooking for forty maniacs living together that didn’t know each other and forty guests a day.” She went on to successful careers in the restaurant business and construction. “How can you say it failed?” she asked the audience. “It was a university. We got to be ourselves. By building my own home at nineteen, I became a builder for forty years. It didn’t fail. We’re still here.”

Richert, whom Westword art critic Michael Paglia has described as one of Colorado’s “most accomplished and most heralded artists,” sees the influence of Drop City in many areas of artistic endeavor, including his own. “As far as I can tell, we were using fractal systems before anybody else,” he says.

The Droppers were pioneers of artwork incorporating ideas about fractal geometry and five-fold symmetry, and even claim to have published the first underground comic book. A broader case could be made that the experience, to the extent that it was the expression of a counterculture yearning to shed the constraints of American consumerism and return to the land, helped pave the way for Earth Day and the recycling movement, Occupy Wall Street and tiny houses — and even Richert’s own current quest to establish a co-housing venture for artists in the Denver area, a place where artists would have their own private residences but share common areas, much like the original vision of Drop City.

“A lot of people called it an experiment,” Richert says. “But art is experimental. For me, it was more experimental art than commune.”