The old socialist model gets a modern twist as intentional communities make educational and social inroads in underprivileged Israeli neighborhoods.

Members of Kibbutz Mishol in Nazareth Illit

Members of Kibbutz Mishol in Nazareth Illit

Guy Gardi, a founding member of 25-year-old urban Kibbutz Beit Yisrael in the southern Jerusalem neighborhood of Gilo Aleph, doesn’t consider himself a pioneer like the founders of the nearly 100-year-old Kibbutz Ein Harod in the Jezreel Valley, where he grew up.

Those original egalitarian communes (kibbutz means “gathering” or “collective”) struggled to establish fertile farms in long-barren soil, while today’s urban kibbutz is an intentional community working to improve quality of life and education in underserved neighborhoods. It’s a different kind of pioneering.

“The unique idea of an urban kibbutz is to take the old idea of a kibbutz — a group of people living together and sharing their resources to help each other accomplish a mission – and apply it to a social environment rather than an agricultural environment,” explains Gardi.

Five secular and religious families started Kibbutz Beit Yisrael in 1993. They moved into a former immigrant absorption center in a rundown part of Gilo and extended a hand to residents of the surrounding public-housing projects.

“We’re working with amazing people who happen to have a lot of troubles. To understand them we have to live among them, respect them and build trust. The connection has to influence both sides,” Gardi tells ISRAEL21c. “Of all the things I do, the most important is just to live there and be a caring friend and neighbor.”

Members founded the Kvutzat Reut nonprofit as a vehicle to promote social action and religious pluralism in Gilo Aleph. Guy Gardi, center, speaking at an event in the community garden built by members of Kibbutz Beit Yisrael for local residents.Kvutzat Reut-Kibbutz Beit Yisrael offers informal education programs for all ages; revitalizes public preschools and elementary schools with declining enrollment; and founded Mechinat Beit Yisrael, a pre-army leadership, study and local volunteering program that attracts students from Israel and abroad.

Guy Gardi, center, speaking at an event in the community garden built by members of Kibbutz Beit Yisrael for local residents.Kvutzat Reut-Kibbutz Beit Yisrael offers informal education programs for all ages; revitalizes public preschools and elementary schools with declining enrollment; and founded Mechinat Beit Yisrael, a pre-army leadership, study and local volunteering program that attracts students from Israel and abroad.

“Kibbutz Beit Yisrael was one of the first to invent this model and a lot of people have come here to learn about it in the past 25 years,” says longtime member Omer Lefkowitz. “Israel is full of people looking for vision, for a life of meaning. Mission-driven communities give them a way to do that.”

A new social movement

Nomika Zion, founder of urban Kibbutz Migvan in the blue-collar southern town of Sderot, estimates that more than 200 urban kibbutzim or similar intentional communities exist across Israel. More are springing up all the time.

“It’s a new social movement,” she says.

This movement includes Garin Torani communities of religious young families; student volunteer villages of the grassroots Ayalim Association in the Negev and Galilee; and non-Jewish (including Druze) intentional communities.

Nomika Zion, founder of urban Kibbutz Migvan in Sderot. Photo by Yossi Oren“What they have in common is that they are extremely involved in their city or town’s social welfare and education,” Zion tells ISRAEL21c. “Most don’t have a sharing economy like classic kibbutzim but they often work and live together.”

Nomika Zion, founder of urban Kibbutz Migvan in Sderot. Photo by Yossi Oren“What they have in common is that they are extremely involved in their city or town’s social welfare and education,” Zion tells ISRAEL21c. “Most don’t have a sharing economy like classic kibbutzim but they often work and live together.”

Zion frequently hosts foreign visitors, reporters and university students wishing to understand the phenomenon. She starts with her own story as a third-generation kibbutznik.

“Israel is full of people looking for vision, for a life of meaning. Mission-driven communities give them a way to do that.”

“I was raised on social values of equality, but nearby there was a development town of North African immigrants we never met. I wanted to break down the metaphorical wall,” Zion says. “I wanted to bring the kibbutz into the city and share my life with people of different backgrounds, and try to build relationships not based on patronizing anyone.”

Six young pioneers followed Zion to Sderot in 1987. At that time, many children of the town’s original Moroccan immigrants were growing up and taking leadership roles to improve life in Sderot.

“There were exciting changes happening and we wanted to be part of that,” says Zion. “When we started we got no support from the Kibbutz Movement or the government. But we wanted to create a new kind of communal model in Israel.”

Kibbutz Migvan members lived in public housing for 14 years before buying land and building their own houses and community center.

They established the first high-tech company in Sderot. The owners from the kibbutz and the workers from town earned equal salaries and made management decisions democratically.

In 1994, they founded the Gvanim Association to provide equal employment and education opportunities for Israelis with special needs. In 2008, they built houses for about 20 people wit Members of Kibbutz Migvan in Sderot built their own neighborhood within the city.h physical disabilities to live among them.

Members of Kibbutz Migvan in Sderot built their own neighborhood within the city.h physical disabilities to live among them.

Today, the high-tech company and Gvanim are independently run. Many of Kibbutz Migvan’s 100 members are involved in these enterprises but are free to work wherever they choose.

Without sacrificing shared activities such as meals, childcare, holiday celebrations and educational seminars, the economic and social structure has become more flexible just as it has on many of the 250 traditional kibbutzim across Israel.

“Over the years many families joined us but didn’t want to have a shared economy, so today only six families are in that shared economy and the rest are not,” Zion explains. “Everyone is very close to one another despite their differences. People contribute in different ways.”

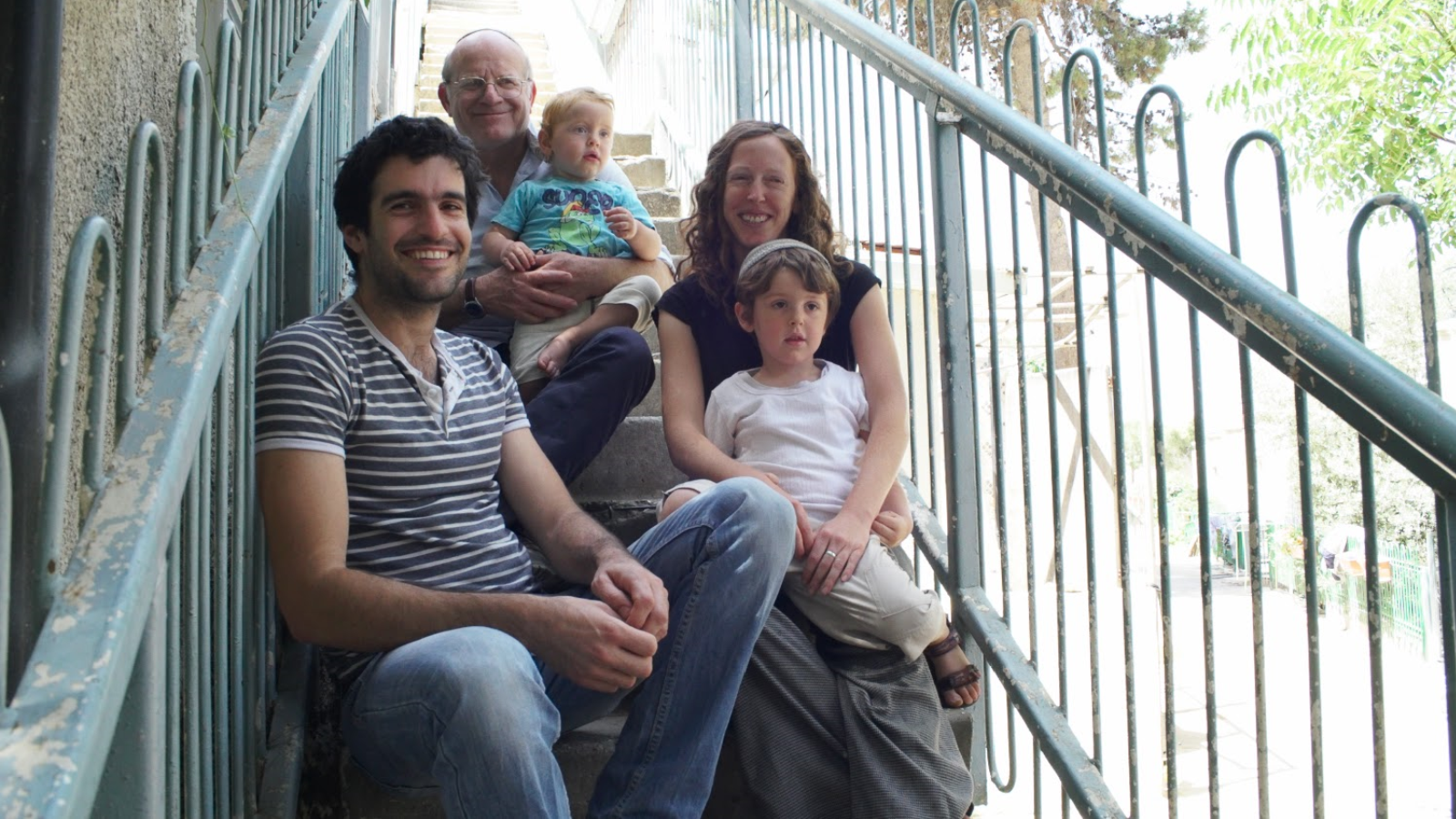

Four generations of the Simon family, all Kibbutz Beit Yisrael members, on the steps of their communal home in Jerusalem. Photo: courtesy

Four generations of the Simon family, all Kibbutz Beit Yisrael members, on the steps of their communal home in Jerusalem. Photo: courtesy

A similar shift has taken place at Kibbutz Beit Yisrael in Jerusalem. Its 10 core families are supplemented by an economically independent group of 60 to 80 families who help carry out Kvutzat Reut’s programs. Mechinat Beit Yisrael currently has 60 men and women in the first year and 25 in the second year.

Lefkowitz, now 40, graduated from the first class of Mechinat Beit Yisrael and came back after the army in 2002 to join the urban kibbutz. He teaches at the academy and directs the activities of alumni who have so far started six similar urban kibbutzim around Israel.

Many of the at-risk neighborhood kids who benefited from Kvutzat Reut programs also come back after the army and become partners in improving the neighborhood.

“The social projects we do touch more and more people,” Lefkowitz says. “It’s not a project; it’s life. You need people that see it as a mission.”

Building Israeli society together

In an impoverished neighborhood of the northern town of Nazareth Illit, 150 members of urban Kibbutz Mishol — half of them children – reside in an eight-story former immigrant absorption center.

About 20 percent of their neighbors are senior citizens. Immigrants from the former Soviet Union, Arab Muslims and Christians are the predominant populations groups here.

The former immigrant absorption center that houses Kibbutz Mishol in Nazareth Illit.

The former immigrant absorption center that houses Kibbutz Mishol in Nazareth Illit.

“We started about 20 years ago,” says founding member James Grant Rosenhead, 44, a 1999 immigrant from the UK. “We work with all the populations together, in a neighborhood where there’s a lot of racism, and bring kids to an ability to build Israeli society together.”

Members of Kibbutz Mishol run and staff the local elementary school, the flagship project of its NGO, Tikkun, whose projects also include children’s afterschool programs and a drop-in youth center. They will build an educational greenhouse at the school this year.

Kibbutz Mishol founding member James Grant Rosenhead.

Kibbutz Mishol founding member James Grant Rosenhead.

Tikkun took over HaMahanot HaOlim, a national youth movement founded in 1929 to help establish agricultural kibbutzim, to prepare young Israelis from its 50 branches to found intentional urban communities.

“We now have a network of six activist kibbutzim – ours in addition to kibbutzim in Rishon LeZion, Eilat, Migdal HaEmek, Haifa and the Jordan Valley,” Rosenhead tells ISRAEL21c. “We help them establish educational and social projects in their neighborhoods.”

Eighty percent of adult Kibbutz Mishol members choose to work in Tikkun projects locally and nationwide. Rosenhead, formerly the joint CEO of Tikkun, recently retrained as a computer programmer to work in the kibbutz’s database development startup.

Hazon, the US-based Jewish Lab for Sustainability, is launching a project to introduce potential diaspora intentional communities to existing Israeli ones. Rosenhead will be a guide for these visits.

“People think human beings don’t share and cooperate well, but it turns out that it is possible to compromise, cooperate and form an intensive community life,” says Rosenhead.

Adds Zion, from Kibbutz Migvan: “When you create a new social model for life, it’s very romantic. Then you meet reality and there are many compromises and disappointments. And yet, I couldn’t have dreamed 33 years ago that the reality would be better than the dream.”